The Legal and Geopolitical Consequences of the U.S. Not Ratifying UNCLOS and Their Effects on Blue Economy Investments

- U.S. non-ratification of UNCLOS excludes it from ISA governance, blocking seabed mining licenses and creating legal conflicts with international norms. - Reliance on domestic DSHMRA law risks litigation and undermines "common heritage" principles, fragmenting regulatory standards with global rivals. - Geopolitical tensions escalate as U.S. unilateralism challenges multilateral systems, drawing criticism from China and allies over destabilizing ocean governance. - Investors shift to U.S. EEZ projects and

The Blue Economy: Legal and Geopolitical Challenges for the United States

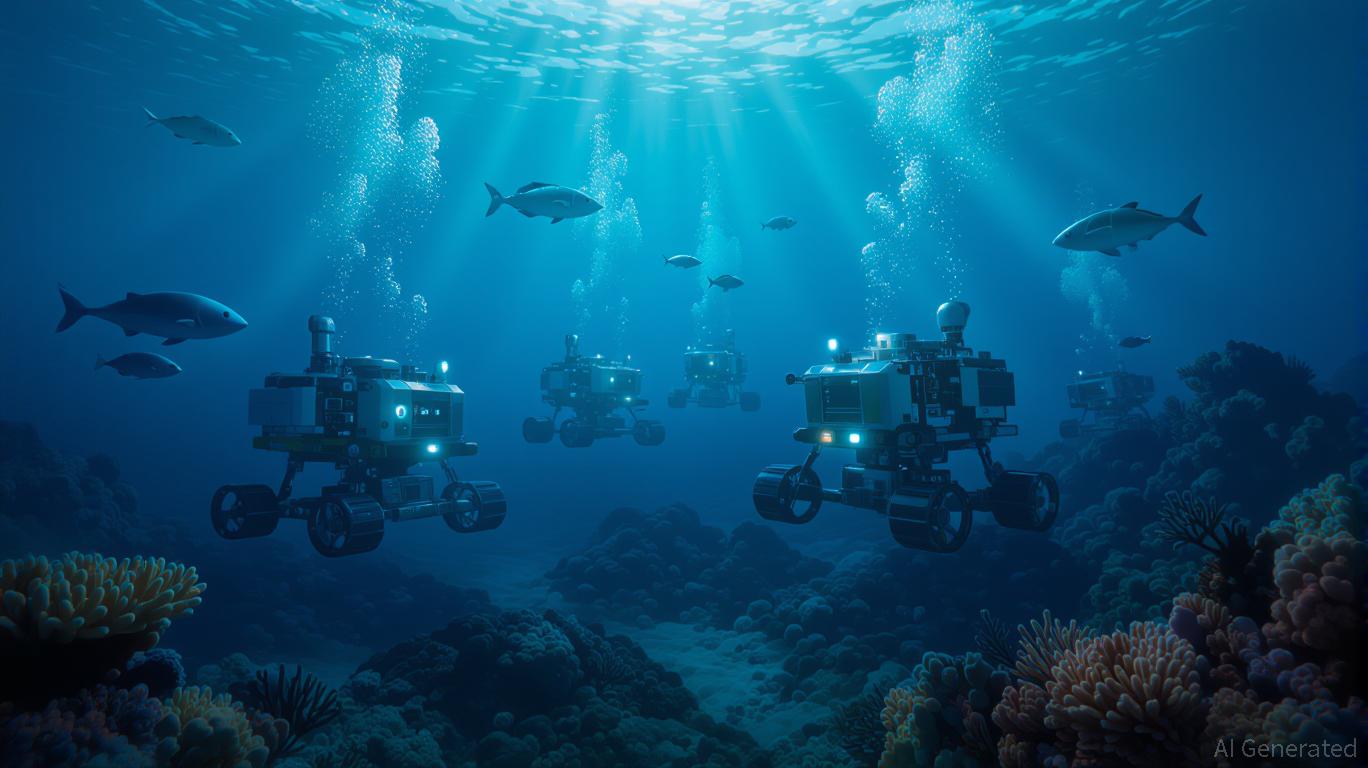

The blue economy, which includes maritime infrastructure, energy production, and resource extraction, is becoming a focal point in both global economic development and international strategy. However, the United States' decision not to ratify the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) has introduced distinct legal and geopolitical complications for its involvement in this sector. These challenges are especially pronounced in the fields of energy and maritime infrastructure, where investment decisions must contend with a patchwork of regulations and rising international friction.

Legal Complexities: Exclusion from International Oversight and Regulatory Ambiguity

By not ratifying UNCLOS, the U.S. is excluded from the International Seabed Authority (ISA), which oversees mineral extraction in international waters. As a result, American companies are unable to obtain ISA-sanctioned licenses for deep-sea mining—an area crucial for acquiring rare earth elements and other minerals vital to the energy transition. Instead, the U.S. operates under the Deep Seabed Hard Mineral Resources Act (DSHMRA) of 1980, empowering the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to regulate mining activities in areas beyond national jurisdiction. This independent approach is controversial, with critics arguing that it contradicts the "common heritage of humankind" principle embedded in UNCLOS and exposes the U.S. to potential legal challenges from environmental advocates and foreign interests.

The lack of a finalized regulatory framework from the ISA further complicates the situation. While the ISA continues to negotiate its mining code, American firms such as The Metals Company (TMC) have sought licenses under DSHMRA, resulting in a split between U.S. and international regulatory standards. This divergence raises questions about environmental protection and the sustainability of seabed mining, which already faces significant technological and ecological hurdles.

Geopolitical Implications: Rising Tensions and Weakening Multilateral Norms

The U.S. position on UNCLOS has also strained its relationships with both allies and rivals. By circumventing the ISA, the U.S. challenges the legitimacy of a multilateral system that is widely accepted by the international community. This has led to warnings from the ISA and criticism from countries such as China, which sees U.S. unilateralism as destabilizing for global ocean governance. Additionally, Executive Order 14285, issued in 2025 to speed up seabed mineral exploration, has been perceived as a direct challenge to the UNCLOS framework, potentially heightening competition in resource-rich areas like the Clarion-Clipperton Zone.

These geopolitical strains are further intensified by the entry into force of the BBNJ Agreement in January 2026. This treaty requires environmental impact assessments and the establishment of marine protected areas in international waters, which runs counter to U.S. priorities focused on resource extraction. Without UNCLOS ratification, the U.S. has limited influence over the implementation of the BBNJ Agreement, further distancing itself from the global consensus on marine conservation.

Investment Strategies: Adapting to a Divided Regulatory Environment

Institutional investors and private equity groups are adjusting their approaches to manage these evolving risks. One method is to focus on maritime infrastructure projects within the U.S. Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), where regulatory processes are clearer. For instance, the Department of the Interior's simplified permitting system for offshore mineral exploration has attracted investment seeking predictable returns.

Another tactic is to form partnerships with nations that hold ISA-approved licenses. Companies like TMC have pursued exploration permits in the Cook Islands' EEZ, utilizing local regulations to avoid U.S. legal uncertainties. This strategy reflects a broader trend among investors, who increasingly favor jurisdictions with stable governance to reduce exposure to geopolitical instability.

Nevertheless, these approaches come with limitations. Concentrating on the U.S. EEZ and those of allied countries restricts access to the most abundant mineral resources found in international waters, where competition from China and other ISA members is growing. Environmental concerns, such as the potential for habitat destruction and sediment plumes from seabed mining, remain unresolved, prompting some investors to take a cautious, long-term perspective given the ongoing technological and ecological challenges.

Conclusion: Navigating Between National Interests and Global Norms

The U.S. decision not to join UNCLOS has created a complex situation: while aiming to secure vital minerals for national security and energy needs, its go-it-alone approach risks undermining the international frameworks that support stable resource management. For investors, the key challenge is to weigh immediate opportunities in domestic and allied markets against the broader risks of regulatory fragmentation and geopolitical backlash. As the BBNJ Agreement and ISA regulations continue to evolve, the U.S. may find itself increasingly isolated from the very system of rules it helped establish—an issue that will shape investment in the blue economy for the foreseeable future.

Disclaimer: The content of this article solely reflects the author's opinion and does not represent the platform in any capacity. This article is not intended to serve as a reference for making investment decisions.

You may also like

The Convergence of Social Justice and Renewable Energy Implementation in Developing Economies

- IEA data shows emerging markets need $45B/year by 2030 to achieve universal clean energy access, with Africa and Asia facing the greatest demand. - Renewable projects in low-income regions demonstrate nonlinear ESG impacts, with solar microgrids directly reducing energy poverty for 600M+ Africans. - PIDG's $27M guarantees mobilized $270M in African renewables, proving blended finance models can de-risk investments while creating 200-300MW capacity. - Kenya's M-KOPA and Indonesia's JETP showcase scalable

Stanford’s top journalist challenges Silicon Valley’s startup scene, calling out its obsession with wealth

PENGU Token Experiences Rapid Growth: Could This Signal the Onset of a Bullish Trend in Cryptocurrency?

- PENGU token's 25% surge since Nov 2025 sparks debate over altcoin revival vs speculative frenzy. - Technical indicators show mixed signals with bullish patterns but bearish RSI divergence and compressed Bollinger Bands. - Whale accumulation and $4.3M institutional inflows contrast with broader altcoin weakness (ETH -27%, SOL -31%). - Upcoming 41% supply unlock on Dec 17 poses $288M selling pressure risk amid fragile market conditions. - Token's future depends on sustaining institutional support, navigati

Clean Energy Market Fluidity: How REsurety's CleanTrade Platform is Transforming the Industry

- REsurety's CleanTrade platform, CFTC-approved as a SEF, standardizes trading of VPPAs, PPAs, and RECs to boost clean energy liquidity. - By aligning with ICE-like regulations and offering real-time pricing, it reduces counterparty risks and bridges traditional/renewable energy markets. - The platform achieved $16B in notional volume within two months, signaling maturing markets where clean assets gain institutional traction. - CleanTrade's analytics combat greenwashing while streamlining transactions, en